What, you want a fairy tale wedding? Are you planning on making the mother of the bride dance in red-hot shoes until she falls down dead?

Fairy tales often feature weddings, but generally pass over them in a sentence, no more. Their naturally compressed style lets them handle the dramatic problem of weddings easily -- the problem being that while weddings are moments of high drama and grave importance to the characters1, they are seldom of plot importance except insofar as they happen, and sometimes not even that.

In particular, the dress, the focus of so much discussion in fairy-tale weddings, seldom gets mentioned. Which is historically accurate. Yes, you would try to get a new dress for your wedding, in the most formal style you had occasion to wear. And you would wear it for those occasions for the rest of your life.

Some regions just liked bright colors for the gown. White might be feasible if you were so rich you could afford a dress that showed dirt so well. Others favored colors -- blue, or green, or even black, to be enlivened by your ribbons and flowers for the wedding and other festivities, but also suitable for funerals.

Indeed in some French cultures, you were buried in your wedding clothes. One fairy tale, The White Dove, a variant of Bluebeard, uses this. The heroine sent off the title dove to her family as a prearranged message that she was in trouble. Then she had to stall until help arrived. Her husband kept calling on her to come down to be murdered, and she told him she was putting on another article of her wedding clothes, as if she were resigned to the death and just preparing herself for the coffin.

Obviously, fancy gowns do feature in fairy tales. The heroine going to a ball might have, like Catskin, a coat of silver cloth, a coat of beaten gold, and a coat made of the feathers of all the birds of the air. Or, like All-Kinds-Of-Fur, three dresses, one as golden as the sun, one as silvery as the moon, and one as bright as the stars. Or like Cinderella, clothes made of cloth of gold and silver. Those are for the ball.

Catskin uses the coat of beaten gold to convince her mother-in-law that she's a suitable bride, and All-Kinds-Of-Fur is caught by the king when she doesn't have time to change out of the star dress and tries to hide it under the mantle of all kinds of fur, but whether they wear these garments to the wedding might be implied by the way the tale says the wedding was solemnized quickly. Still, it's not stated.

As for Cinderella, her wedding clothes aren't even hinted at.

Then, those are sentence-long weddings that wrap up a story. Perhaps plot-device weddings, which actually are significant in what they change, have more?

Sometimes they are worse, actually. In The Goose Girl and other tales where the villainess usurped the true bride's place, the tale can talk about the bride and bridegroom without ever mentioning whether they went through a formal wedding or are regarded as betrothed.

(Historically, "betrothed" was a lot more serious than an engagement today. There was, in fact, a fuzzy boundary between "betrothed" and "married.")

In other stories, such as The Wonderful Birch, Brother and Sister, or The Girl Without Hands, the sentence-long wedding merely marks the transition into a different part of the story. She and her husband live peacefully together, and perhaps even have a baby, before the villain of the first part, or someone angry about her marriage, causes more trouble.

On the other hand, plot-significant weddings can occur. Famously, Snow White's wedding features her step-mother -- or mother, in the Grimms' first version -- being forced to put on red-hot iron shoes and dance until she drops down dead.

Or again, Cap O'Rushes gives orders to the cook that he is to use no salt in any of the wedding dishes, though the cook warns it will make the meal "rare nasty," and so brings to bear on her father, a wedding guest, what she meant when she said she loved him as meat loves salt.

Then there's the ones where the heroine is married off to an animal bridegroom, and goes back to visit her family. Sometimes, as in The White Wolf or The Singing, Springing Lark, this is because her sisters are marrying. Which is of no plot significance whatsoever except insofar as it provides an excuse. The heroine can visit out of homesickness for the same reason.

The hero in a similar match always visits out of homesickness, never to attend a wedding in his family. Go figure.

What these heroes and heroines do have in common in that, having lost their love interest because of the visit, they then cross thrice ten kingdoms, or serve for seven years, climb the glassy mountain, and wring the bloody shirt, or what have you. Finally, they arrive, and almost always as the love interest is about to marry the false bride, or the false bridegroom as the case may be.

When the heroine and her love interest just run away after she disenchants him and so restores his memory, this is just background detail, but if there's a show-down, it happens at the wedding. Whether it's The Three Princesses of Whiteland with the result

Then up rose the Princess from the board at once.

"Who is most worthy to have one of us," she said, "he that has set us free, or he that here sits by me as bride-groom."

Well they all said there could be but one voice and will as to that, and when Halvor heard that he wasn't long in throwing off his beggar's rags, and arraying himself as bride-groom.

"Ay, ay, here is the right one after all," said the youngest Princess as soon as she saw him, and so she tossed the other one out of the window, and held her wedding with Halvor.

or The White Wolf with the result much the same:

But he said nothing, for he waited till the next day, when many guests — kings and princes from far countries — were coming to his wedding. Then, when all the guests were assembled in the banqueting hall, he spoke to them and said: 'Hearken to me, ye kings and princes, for I have something to tell you. I had lost the key of my treasure casket, so I ordered a new one to be made; but I have since found the old one. Now, which of these keys is the better?'

Then all the kings and royal guests answered:

'Certainly the old key is better than the new one.'

'Then,' said the wolf, 'if that is so, my former bride is better than my new one.'

And he sent for the new bride, and he gave her in marriage to one of the princes who was present, and then he turned to his guests, and said: 'And here is my former bride' — and the beautiful princess was led into the room and seated beside him on his throne. 'I thought she had forgotten me, and that she would never return. But she has sought me everywhere, and now we are together once more we shall never part again.'

In neither of those, or tales like them, does the actual wedding unfold, except as a sentence or two.

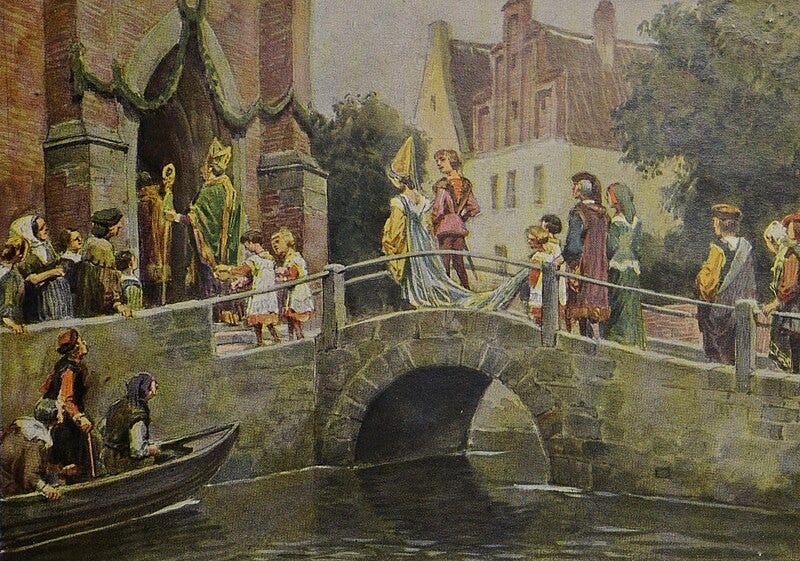

Then, there's Maid Maleen. True, her story does nothing more than speak of "the bride's magnificent clothes and all her jewels" but it has the bridal procession to church. This is because Maid Maleen is both the true bride and a false bride.

She and the prince loved each other, and her father locked her in a tower for seven years because he wanted her to marry someone else, and her prince agreed to a marriage because he believed her dead.

On the other hand, the new bride told her to take her place at the wedding to hide her ugliness -- or, in other variants, her pregnancy. The procession affords her chances to hint at the truth, and finally lay claim to her prince.

Then, some variants of Rapunzel assure us the prince and Rapunzel married before she became pregnant, while still in the tower. If this strikes you as highly improbable bowdlerization, it is yet possible.

In the Middle Ages, particularly after the Dark Ages, it was the words of marriage -- the man saying, in some form, "I take you as my wife," and the woman saying likewise, "I take you as my husband" -- that made a marriage. It was highly discouraged to do this without witnesses, and in places other than the church door, but it was valid.

Not until early modern times were witnesses and like requirements added, to make it easier to figure out whether a marriage occurred, so the fairy tale would just have to happen before then.

Though there's no problem with the variants where the maiden in the tower and the prince think to run away before the witch returns. Then they can marry after their escape -- perhaps after she disenchants him and restores his memory before he marries another -- and get a one-sentence wedding before they live happily after.

"The wise old fairy tales never were so silly as to say that the prince and the princess lived peacefully ever afterwards. The fairy tales said that the prince and princess lived happily ever afterwards; and so they did. They lived happily, although it is very likely that from time to time they threw the furniture at each other."

― G. K. Chesterton

For more on them, see

Romance And The Royal

A number of fantasies set in fairytale land -- at least in my experience -- talk as if all princesses must marry princes, and vice versa. It is a serious constraint on the characters.

Nice analysis.