You have it in hand, the triumphant ending, the glorious way the hero will defeat the villain and usher in the age of gold where he can marry his love interest in peace.

Now you just need the entire rest of the story.

Take notes. Put down the scene, the hero, the villain, the love interest, and any other characters who appear in it.

Then, remember that the characters are who they are in that scene. One thing you will need to do to prevent its dominating their characterization. That is how they react when facing the situation at the climax. They react differently in different situations.

If the love interest is aghast at what the villain does at that moment, the rest of the story should not simply show her horrified by violence. It should show her other facets, her sensible refusal to let the heroes commit themselves when weak and her stern ability to enforce it, her tender concern for the wounded, her brave stand against attackers to buy time for reinforcements. Building up her character to show how stalwart, resourceful, and courageous she is will let her horror hit with full force.

If, on the other hand, her part is to make an ineffectual attack that provides a valuable distraction, building up that she's a scholar or a healer or otherwise valuable out of combat, to emphasize that even that gesture was grand. If she's also sagacious about staying out of battle, entering the fray makes it clear how desperate things are.

And, of course, her role, and everyone else's role, has to serve the needs of the story. All the characters have to be fleshed out to make them three-dimensional, and the only way to do that is to have them appear in different situations where their other facets will appear, while moving the story forward.

In particular, consider what trait the hero most needs to face the villain. Then ensure that he does not start out with it. This gives him a character arc, and thus we get to see him growing.

It helps for similar things with the other characters. Not only what events could lead to the climax, and who can be relied on to play their parts, but who would find these events deeply meaningful.

This is also needed to build up the conflict. Even if the hero doesn't get a character arc, you need to build up conflict. The villain must be portrayed in action as dangerous and evil. The hero and allies must be valiant, determined, and helpless. Things must go well for the villain on several occasions, and the heroes face set-backs.

These need to be plausible.

The grave problem with this is thinking yourself back into the ignorance of the characters. You know how it will end, and they do not. They need to wonder, to doubt, to pick a means of fighting that does not look insane based on what they know, and to fail convincingly.

The greatest danger to it is the leap of logic. I have read stories where it was obvious that the writer started with the ending, and worse, the ending was about making a discovery. The reason I could tell is that the characters guessed at things. And they never ever guessed wrong, no matter how odd the truth was, no matter how insufficient the evidence, no matter how far the leap had to go to get to the answer.

Plant evidence. Plant sufficient evidence to justify guesses, but don't make all the guesses right.

And while doing all this hard work to build up to your ending, remember this: you don't have to end the story that way.

There's the little issue of its possibly being in a different place in the story, in the middle or perhaps even the beginning,1 but it's more than that.

It's one of the most annoying things about inspiration. The very thing that starts off the story may not work as the story itself grows and develops. Especially if the original inspiration still sparkles and fizzes and sparks in the corner. Sometimes you have to spin off the story and work on another in hopes or curbing the original inspiration.

But the story must stand as a whole, with the ending only as the glorious culmination of all that lead to it.

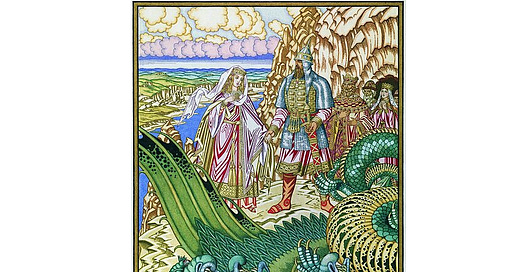

See this:

Inspiration and Aristotle

When dealing with inspiration from scenes, or parts of scenes, trying to develop them into a full story, it is wise to remember Aristotle's dictum.