Wizardry For The Compleat Idiot

How smart does a wizard have to be?

All those books, all that study -- how smart does someone have to be to master magic?

Well, we do have the Danish fairy tale Master And Pupil where the answer is “smart enough to lie about being able to read after having been rejected once.”

On the other hand, learning to read was not that common a skill once upon a time. And the widespread tale of the sorcerer’s apprentice shows the difference between a smattering and full knowledge. Or possibly learning and wisdom. Though he still had to be able to read.

Even the sort of witch who lived in a cottage in the village, or near it, required wits.

Where magic really can unfurl its abilities is in objects that can be used by anyone. Even if the wizard can set them to be used by only people of a certain character1 and can even determine their character,2 what about their wits, and their knowledge?

This is not quite so important as how easy it is to make them,3 provided that the ability to use them is somewhat common.

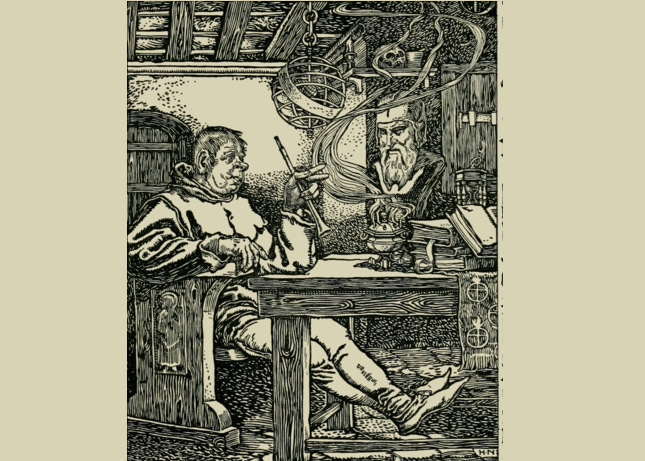

Old-school sword and sorcery, to be sure, often filled the sorcerer’s tower with crystal balls and magical wands that only the sorcerer himself could use. Or, at least, that only the sorcerer did use.

Still, it had magical things like boots and cloaks and ropes useful to the thief. And if their means of manufacture was such that only a knave would use them, the heroes of sword and sorcery were notoriously less than heroic.

But if the mighty sorceress creates a wand that any old hedge witch can use to lob fireballs at the enemy, all the king needs to do is recruit hedge witches, and his only problem is that since he’s giving her the ability to lob fireballs, he has to keep her happy.

He might, as a consequence, prefer that it require more study. Perhaps enough so that the aspiring wand-wielder would have to spend several years in dedicated study. That would give the student a stake already in society, without the king’s having to give him anything. Probably more would be wise, there’s only so much that you can demand from duty, and besides, rewards encourage others to do the same. But it would be less costly.

Or maybe it can’t be curbed like that. Maybe you need locks and bolts and thick doors and heavy chests, and spells that scream whenever someone unauthorized tries to get at the object. Stone dogs -- or lions -- that come to life and savage the intruder. Spells that paralyze, or petrify, or trap in spider webs of astounding strength.

And, of course, ways to identify yourself, by password or by appearance, because otherwise, there’s no point to creating the object in the first place. (Barring accidents while creating. Given that the number of badly made magical objects in fantasy is quite small4 -- and it’s a trope unknown in the source material -- that would take some work on its own.)

Maybe you need a powerful spell to dissolve magic all about your tower, because with all the problems it brings, it’s the only way to keep some utter idiot from getting in and asking stupid questions of the enchanted brass head that answers questions -- and worse, listening stupidly to them, because it does tend to talk in a subtle, abstruse manner, full of many fine distinctions.

The great nightmare, of course, is for a fool to inherit such objects. Whether lacking in intelligence or not. What is required is sufficient judgment to tell whether you can use the object wisely.

The dread of a wizard may be the royal order to make something for the fool of a crown prince. The brass head may speak in a subtle, abstruse manner, full of many fine distinctions, in hopes that it will not enable the prince’s notable follies, because, as Machiavelli so sagely observed, a prince who is not himself wise can not be wisely counseled.

The order for a fireball wand, on the other hand, may require evasion. Or simply running away. After all, if the kingdom burns up in fireballs, the wizard would have to leave anyway.

Such are the problems with magical objects.