In which I continue to talk about counterproductive practices of treating fiction and RPGs as if they were the same sort of medium.1

One thing that militates against it is that it's a lot easier to be mysterious about the world when writing than when running a game.

Inexplicable characters.

Anomalies.

Magic that does not fit the rules -- whether it's a wizard wielding the spells, or a magical sword cutting what nothing should cut.

Superpowers with ambiguous origins that may or may not fit in the normal metaorigin.

A monster whose powers are vague -- or whose type is vague.2

A DM, of course, can use magic that does not appear to fit the rules, but the players are justly quick to deem that cheating. It is a mystery in the genre sense, and if it is not a fair-play whodunnit, they will not like it. Far worse if it is used to attack them, and it does not even fit in normal monster parameters.

A writer does not have to fit a character's magic into the system. Or an object's. It takes skill, it takes rhetoric, it takes careful handling of any plot consequences, but a mysterious form of magic can touch the characters' lives, soften the edges of the hard magic system, add a touch of wonder.3

(At that, I have seen fiction writers remove mystery from their worlds just as the time they release an RPG based on it. The rules, I suspect.)

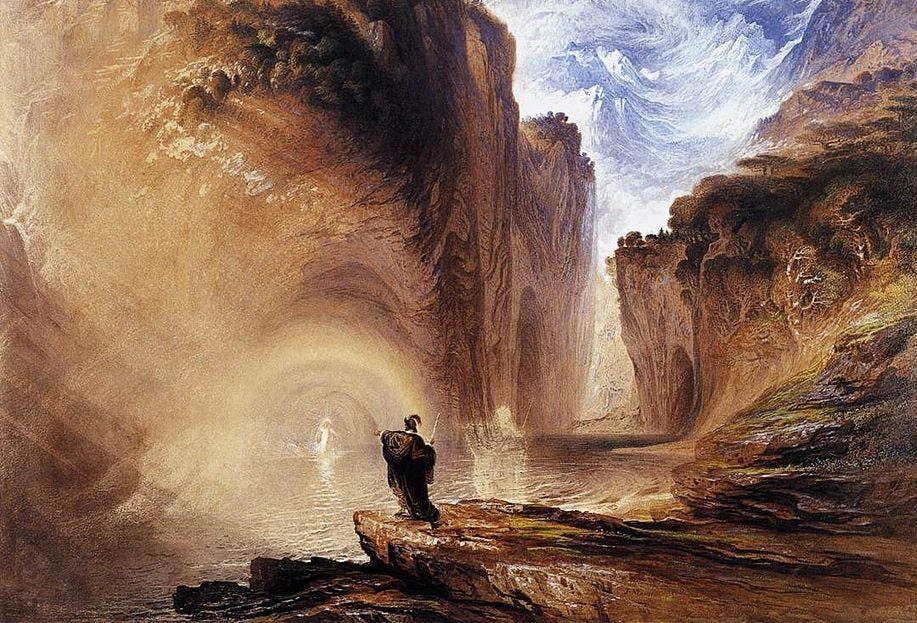

In writing, there is more time to deploy the rhetoric and so to relish the numinous, the uncanny, the mysterious. In the middle of a dreaded grove, where birds do not sing, where no squirrel or rabbit scurries across the forest floor and rustles the dead leaves, where not so much as an insect flits, where the trees grow so thickly as to leave the entire forest floor in darkness so deep that neither moss nor ferns grow, where mists coil about in the midst of the day, the story can dwell on it, and on the characters' reactions to it, which underscore it.

When a snake hisses in this silence and stillness, the stage has been set, and the rhetoric can much more easily make this snake a terrible and marvelous creature.

The writer's rhetorical advantage also lies in the way the characters are determined by the writer. If the writer uses a viewpoint character who thinks it's all dullsville and overlooks everything, the mystery is gone except in the mechanical sense. (There are stories where that is a useful thing to do.) But a writer can use a character who stops and observes and dreads.4 A masterful writer can suggest the mystery and wonder that the stupid blockhead is missing, though it takes true mastery.

Characters can also figure out, or stumble on, the right thing to do in the situation. It may appear as a deus ex machina, but it can be disguised, especially if they reflect on their luck. A mysterious riddle can baffle them, even anger them, but an irresponsible knave who not only refuses to try but bullies the other characters who attempt to guess exists only if you put him in there -- and you can make the other characters resist his bullying if it comes that.

You do have to think yourself back into their ignorance here, not only for the usual reasons of not tipping your hand5, but to avoid draining the mystery. Something too clear, too quick, is not mysterious.

On a different side, the story telling doesn't require strict definitions so you can roll the dice. Whether the gloriously singing firebird can fight off the heroes does not matter, because they can stop and listen, and then follow it to the castle.

At that, the fight with the great black dragon of the storm doesn't end in victory because the hero rolled a 20. The writer has to write a convincing battle, by the standards of the genre. (Most fairy tales with dragon-slaying have the fight get a sentence, or perhaps a short paragraph.)

A mysterious force can even work as a plot device at some points.

During the middle of the story, as long as the characters react to it as a strange, uncanny thing happening to them out of the blue, it can affect their lives for better or worse. (Though if it's for the better, it would be best if it unnerves them. It may even bring to bear the significance of what they are undertaking.)

Even in the denouement, if the heroes are suffering from their victory, if one of them is dying, perhaps a final benediction and reward for their labors is a mysterious healing that they know is beyond the bounds of magic that they know. (If a supporting character does it, well, stealing a scene like that is not an aesthetic flaw the way robbing players of agency is.)

It's the rhetoric that does the trick. It must suggest that this unlooked-for gift is a blessing, not a contrivance. And this is a tool much more easily taken from the writer's toolbox than the DM's.

Begun here

The DM vs. The Writer, In Character

Every mode of story-telling -- movie, novel, comic book, role-playing game -- differs in what it can tell, and how it can tell it. Learning how to do one may habituate you to useful skills, and to positively counterproductive practices, for another.

and followed up here

The DM vs. The Writer, As A Matter Of Time

In which I continue to talk about counterproductive practices of treating them as if they were the same sort of medium.

"Trolls" covered a lot more ground in the folklore than in the fantasy genre. So much more, in fact, that you could call a human a troll.

Wonder and Magic

The elusive sense of wonder is often put forth as a motive for science fiction and fantasy, but for all the praise bestowed on it, it can be hard to find in SF or fantasy. Then, it is a brilliantly colored but sneaky, sure-footed beastie -- or is a birdie? That would explain how swiftly it can escape nets and fly off. And stories. And books, and authors.

Put Your Words To Work

Description is something all writers have to wrestle with. Once I heard a writer asking how to make his prose more cinematic.

In My Ending Is My Beginning -- I Hope

You have it in hand, the triumphant ending, the glorious way the hero will defeat the villain and usher in the age of gold where he can marry his love interest in peace.

""Trolls" covered a lot more ground in the folklore than in the fantasy genre. So much more, in fact, that you could call a human a troll."

In Michigan, Yoopers (those who live in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, or UP) refer to those who live below the Mackinac Bridge as trolls. Art imitates life/life imitates art!